Frida

The movie biography is a tricky genre. When the subject of the film is an artist then the difficulties are multiplied. All too often, the life of creative endeavour and its psychological inspiration seem to elude the conventions of filmmaking. Even well-made and well-acted biopics tend toward the dutiful and dull. The film critic, A.O. Scott, once put it this way: "we are usually treated to the superficial pageantry of the artist's career - sex and politics, drinking and fighting, celebrity and ruin". But the inner magic of the life too often evaporates. I think that Frida, which was the latest in our international film screenings, largely overcomes these limits. Having watched it many times my affection for the film has actually grown; I like the film enormously. In time it will come to have a greater reputation than some of the initial desultory reviews suggested.

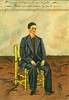

Part of the problem Frida faced on release was the overwhelming baggage of expectation. Obviously, this has much to do with the life and work of film's subject, the great Mexican surrealist painter Frida Kahlo. By the 1980s Kahlo had become more, much more, than simply a wonderful artist who lived through the most turbulent decades of Mexico's history. She had transmogrified - literally - into an icon for every imaginable heterodoxy: a poster girl for bohemianism, a bearer of proto-feminist consciousness, a martyr of suffering, a pop culture legend. These are all valid, if partial, readings of the life and the art. But somehow with Kahlo the reverential iconography came to overwhelm the life and this does not make for a promising biography.

The second burden lay in the making of the film itself. It is now well-known that Frida's star and producer, Salma Hayek, had to fight tooth-and-nail during her seven-year quest to keep hold of a project that was passionately close to her heart. There was a fearful moment when it seemed likely that Madonna (cashing in her dubious credentials for having played the execrable Evita) would get the role. Hayek has said this about her own tenacity:

This was a story that was important for me to tell. It was not just making the movie, it was about making the right movie.No little part of this desire was driven by a powerful sense of Mexican pride:

I think it's a story that shows Mexico in a light that it has never been seen in before. At this particular period of time that Frida lived and was there, Mexico was the nucleus for a lot of sophisticated minds. And I really wanted to show this part of my country and this extraordinary woman who inspired me because of her courage to be unique always in everything she did.And then there was a barely-hidden condescension towards Hayek's own acting capabilities. I think this is a badly misplaced view: while it's true that she has been in some pretty mediocre Holywood fare her earlier work in independent Mexican cinema demonstrated a considerable presence and charisma. More than most, she's been a victim of some lousy material.

Hayek's - and director Julie Taymor's - film generally works well in a difficult genre. It is not an unalloyed triumph or even a great film. But it consistently offers us a sensitive rendition of the core motifs of Kahlo's tempestuous and anarchic life and a transcendent insight into the agony of suffering that produced the art. The story of Kahlo's life is so well-known that it barely needs repeating. In the film her youthful and headstrong obsessions - intoxicated by art, sex and left-wing politics - are nicely captured in small vignettes that establish the heartbeat of the mature woman. But her life was forever changed by two accidents. The first was the streetcar accident in which her back and pelvis were horribly injured and, as Kahlo wryly observes, she "lost her virginity". That central scene is shot with a very powerful, almost hallucinatory intensity. From that defining moment, Kahlo's journey becomes one of self-discovery and self-realisation as an artist. It is a journey dominated (but never overshadowed) by her entanglement with the muralist, Diego Rivera, the second great "accident" of her life.

Through the charismatic characterisation of both Hayek and the bear-like Alfred Molina (who plays Rivera) the film captures the underlying magnetism that brought them together and, somehow, kept them together even through betrayal: the passion for unorthodox left-wing politics, professional artistic respect, and unrdiled sexual attraction. It's a relationship built on abiding loyalty if not fidelity. And it's a heady combination that never falls into triteness or predictability. It's as well that Hayek and Molina are so compelling because some of the other characters (Trotsky, Breton, Rockefeller) are only thinly realised.

Though the raw materials of Kahlo and Rivera's lives would be sufficient to raise the bio-pic way beyond the dutiful, the most interesting aspect of the film is the innovative way that Taymor deals with the art. Kahlo was no realist and neither is Taymor. The narrative is interpolated with wonderful animated sequences - including a Dadaist King Kong scene - that not only (literally) give life to some of the most important paintings but make subtle links to the abiding influences of Mexican folk traditions - fearful dancing skeletons, broken body parts - that so obsessed Kahlo. It is precisely when the film takes these kinds of creative risks - when it moves away from dutiful storytelling to capturing the moods and sensations that marked the life - that it works best: the vital bursts of colour, the glorious music and the over-the-top theatricality mark out Frida from the run-of-the mill. Hayek and Taymor have made the "right film". See it if you can.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home